Saint Jerome in the Wilderness, ca. 1496, oil on wood, 23.1 x 17.4cm, National Gallery, London

Albrecht Dürer is the artist da Vinci would have been, had da Vinci not been so lazy. His accomplishments simply beggar description. He is primarily known to the modern world for his engravings, and they are certainly magnificent creations, but he was much more than a simple draftsman and etcher. His use of color and composition were far ahead of his time. He wrote books on measurement, proportion, perspective. He drew constantly, everywhere. Many of these drawings survive today, but the drawings on which his engravings were based are lost in the process of creation.

Saint Michael Fighting the Dragon, Engraving, ca. 1497, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, Germany

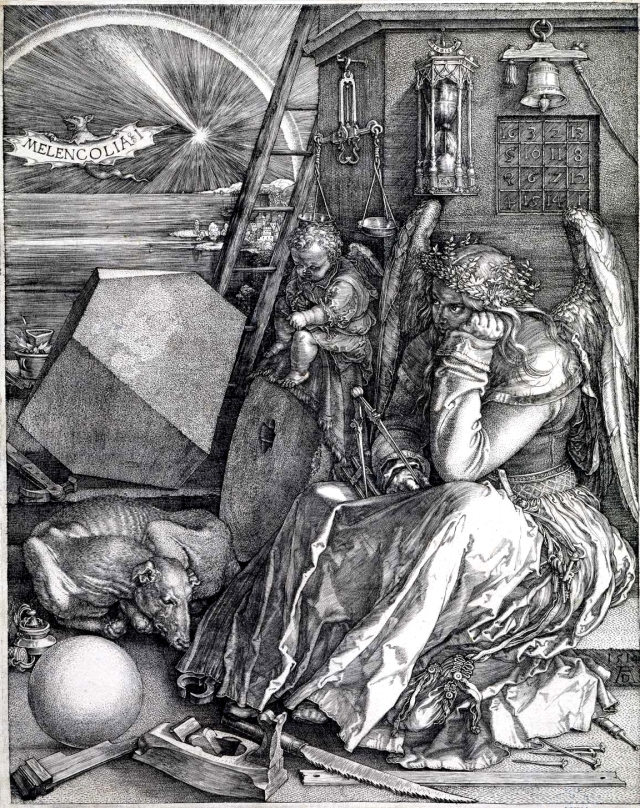

Like da Vinci, Durer liked puzzles, and he included many games and codes in his work. There is a two volume work (two!) written by an art historian and critic just to try and explain the symbols found in his engraving Melencolia 1. The boy was hard at it, pretty much all the time, and we are blessed with a staggering collection of his work to study and marvel at. He is well worth a day of surfing through.

Melencolia 1, Engraving, 1514, 24 x 18.8cm, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, Germany

Sometimes I am entranced, not just by the masterful talent of the artist, but by the dutiful, selfless, and painstaking efforts of all who came after him to preserve his work for posterity. Think of it, small watercolors and bits of paper sheets lovingly maintained for four hundred years. To put that in perspective, pull out some personal folder, say of old receipts or letters from four or five years ago. Look at how they’ve aged and faded in your modern, climate controlled environment. Now imagine trying to prevent any further deterioration for the next four hundred years. Good luck with that.

Dead Bluebird, 1512, watercolor, Albertina Vienna, Austria

For every Durer, El Greco, and da Vinci there were thousands of simple, responsible heroes who faithfully cared for and tended the work of their genius. We treasure the art of Van Gogh but without the persistence and faith of his sister in law, it might all be forgotten, long since passed along in yard sales or lost in fires.

Young Hare, 1502, Gouache and watercolor, 251 x 226mm, Albertina Vienna, Austria

Artists, too, preserve, but they are preserving on a grander, more metaphorical level. They imagine themselves to be keepers of the moment, the guardians of the now. They alone are unafraid to take the whole of eternity and mark notches on it like a proud mother charting the growth of her child. Everything is important to Durer: the metaphysical and the physical, the consternation of the angels and the sadness of the son of god, the alert peace of the wild hare and the fragile, broken promise in a dead bluebird.

When we undertake to pay attention to these artists, to study what they’ve left for us and puzzle over the things they thought to see, we too are contributing to their preservation. They live through our shared experience of their work. They teach us that everything is worth our attention if only we take the time to look at it, and that all of it is worth keeping safe.

I sometimes doubt that Americans understand issues of class at all. Our society is so pugnaciously egalitarian that we imagine tangible assets are what distinguish one set of people from another. But as the English understand class, it has little to do with one’s funds and everything to do with one’s upbringing.

I sometimes doubt that Americans understand issues of class at all. Our society is so pugnaciously egalitarian that we imagine tangible assets are what distinguish one set of people from another. But as the English understand class, it has little to do with one’s funds and everything to do with one’s upbringing.

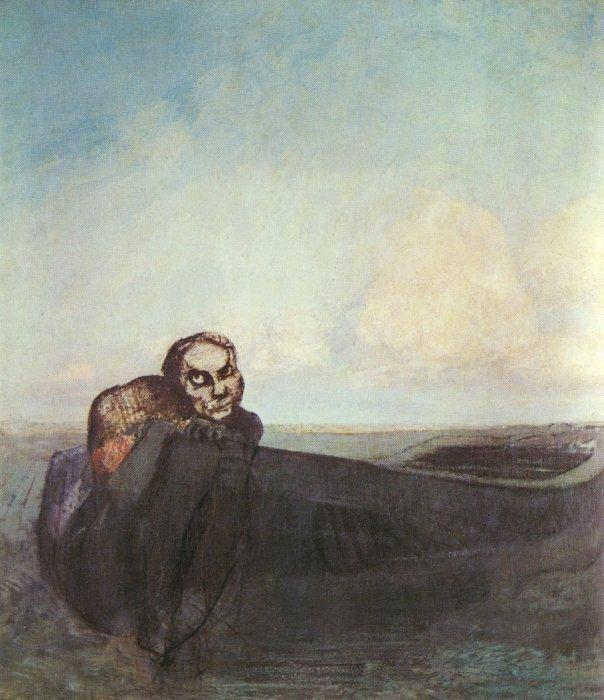

The end of the nineteenth century kicked up a lot of dust in the art world as artists struggled with new ways to share the world of their peculiar and intimate senses.

The end of the nineteenth century kicked up a lot of dust in the art world as artists struggled with new ways to share the world of their peculiar and intimate senses.

Brown Paper Bag

Brown Paper Bag